HTML, the plot thickens

After I wrote my review on several WYSIWYG editors that Linux folks might want to use to hone their HTML and CSS skills, I got several aggressive suggestions for additional products and tools. It was an offer I could not refuse, and you might want to narrate this in a slightly asthmatic voice of Marlon Brando, plus the accent.

Today, we shall expand. And the interesting part it, we’re going deep space, into the Nerdon Nebula, where you get to meet LaTeX-like syntax and similar cool stuff. But the idea is, you will gain a big, fat notch on your proverbial Linux and HTML belts, and this knowledge ought to come useful one day. Let’s continue then, mastering HTML the fun way.

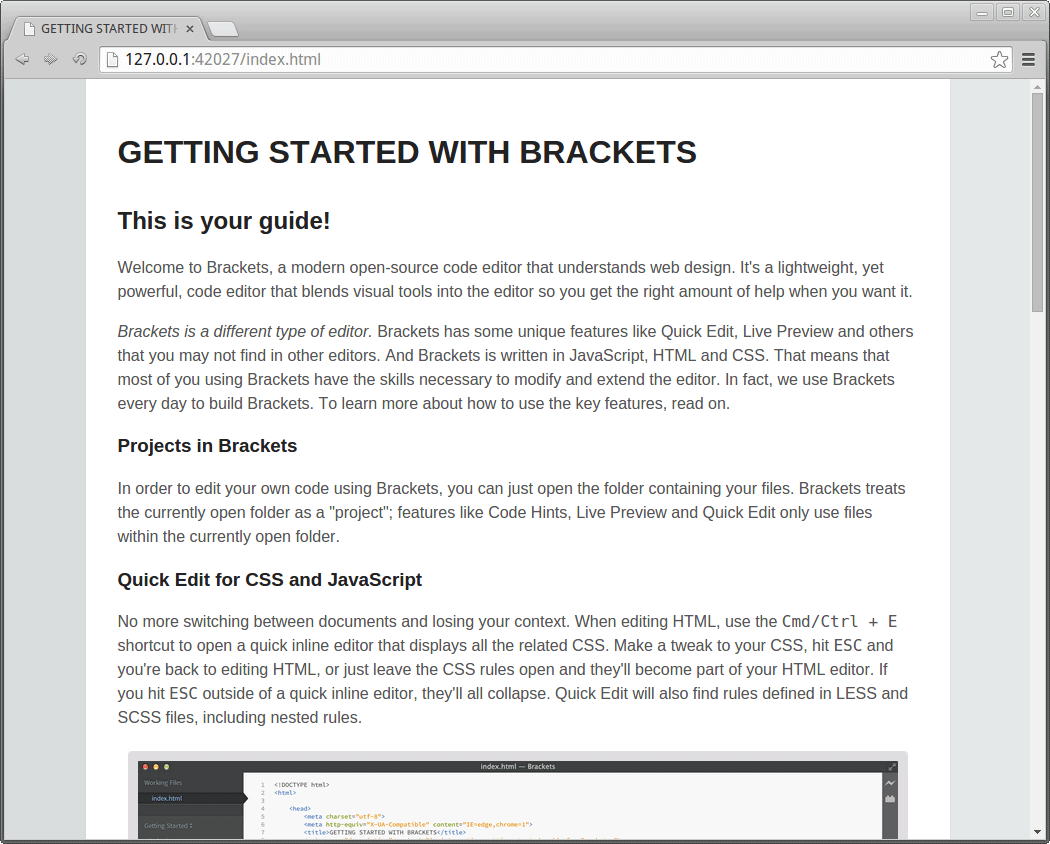

Brackets

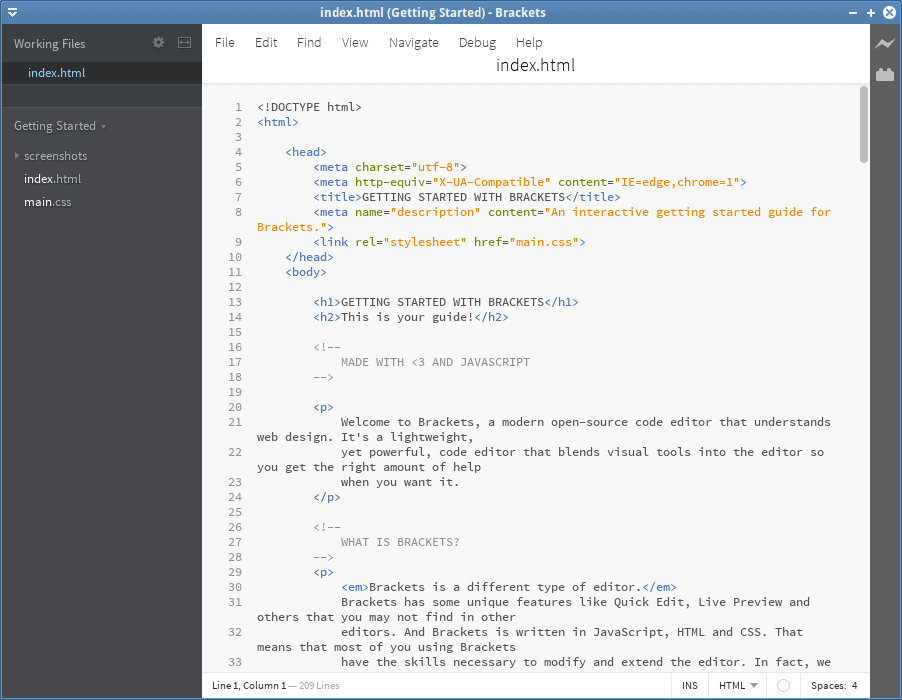

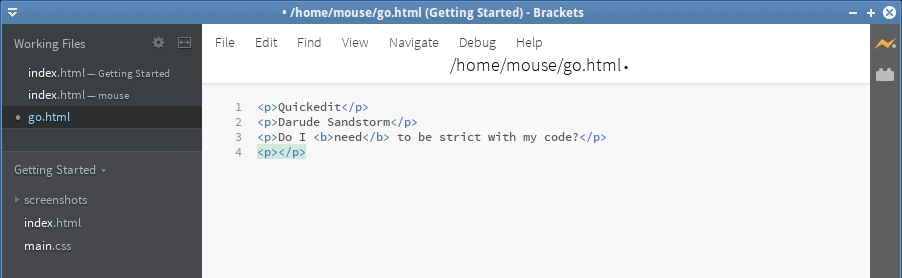

This is an open-source, cross-platform text editor, originally developed by Adobe Systems, and now community maintained. It’s not available in the repositories, but the installation is pretty simple and straightforward. The main view is a little unorthodox, compared to most products you know, with a sidebar for your projects and files rather than a standard tabbed interface. It looks and feels a little spartan, and right away, you do get a feeling it’s more oriented toward skilled users, somewhat like Bluefish.

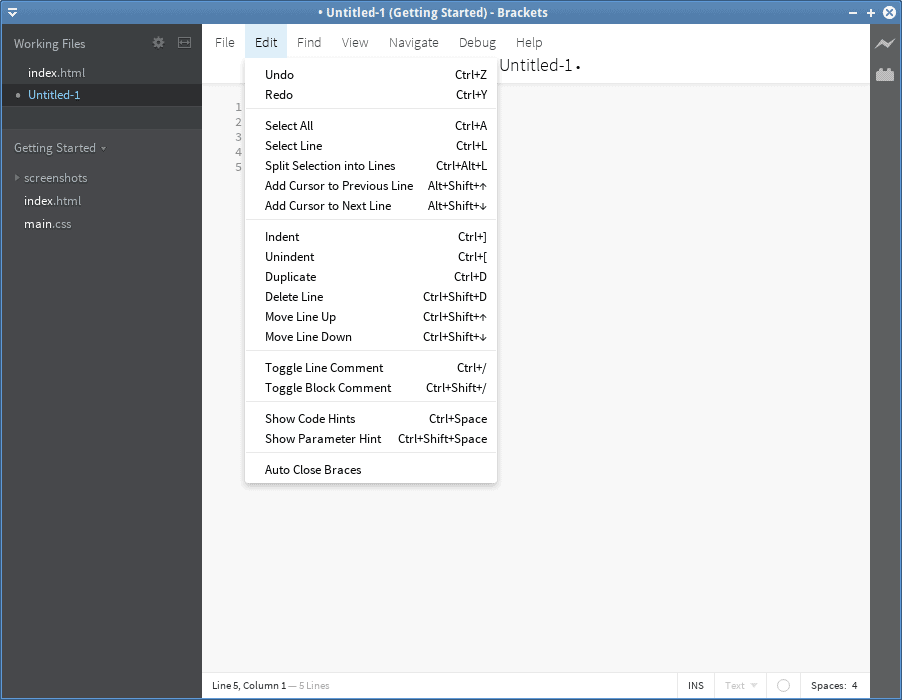

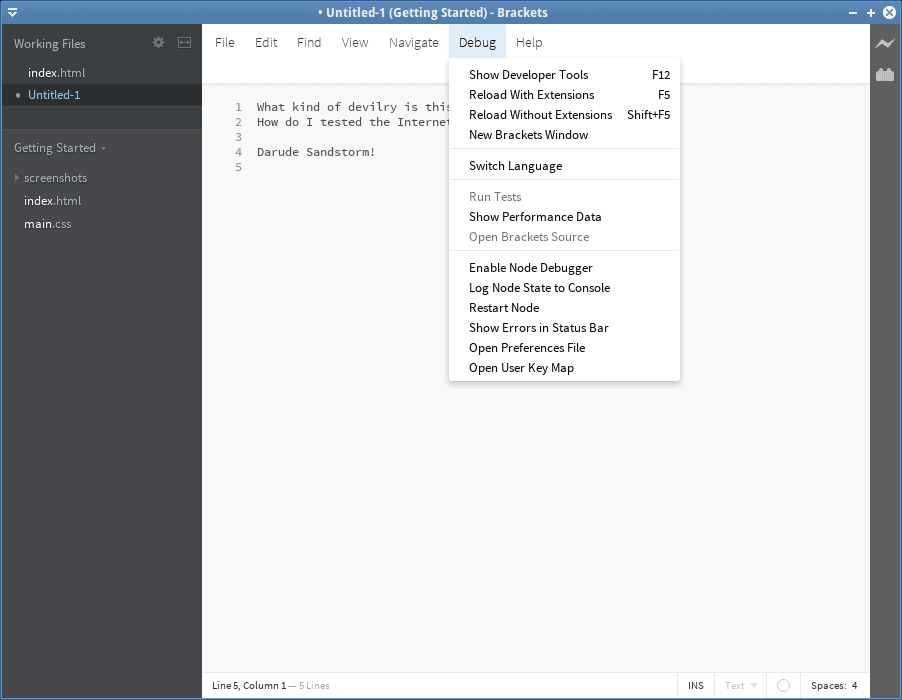

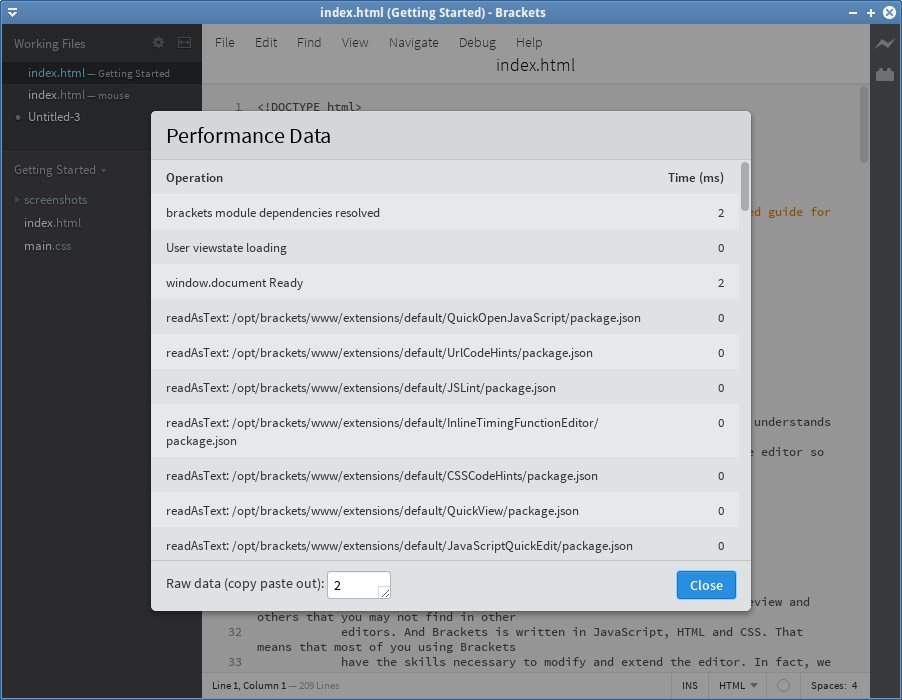

The system menu is rich, and it comes with a lot of options, all accompanied with shortcuts, so you can get really productive. Some of the features are the kind you expect from any decent piece of software. Others are a little more elaborate and advanced. The debug set is pretty impressive. It allows you to reload the editor with or without its extensions – and yes, there are extensions available, somewhat like Notepad++, you can switch language, check performance data, and more.

Extensions

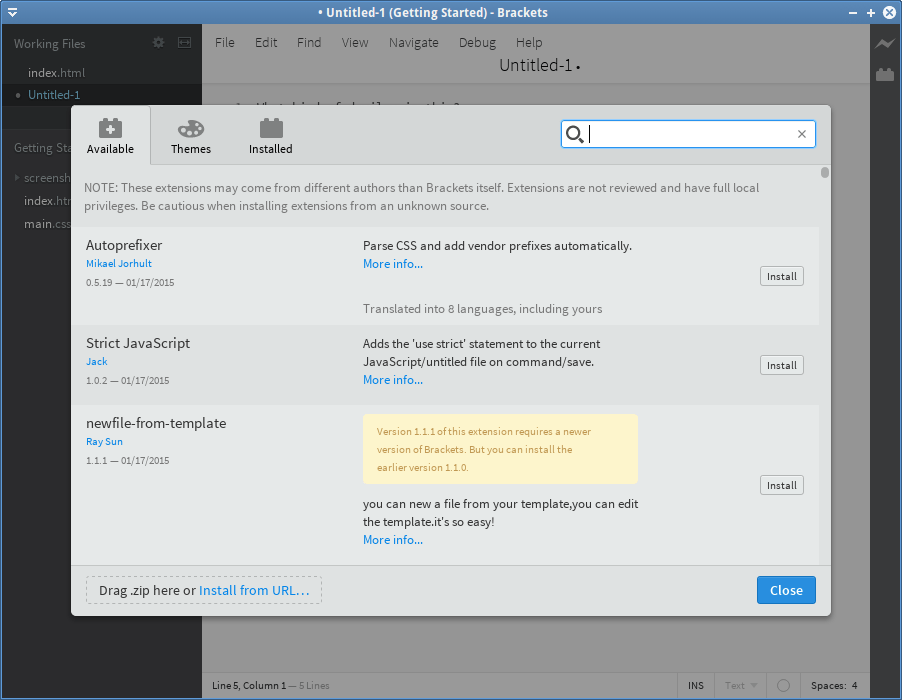

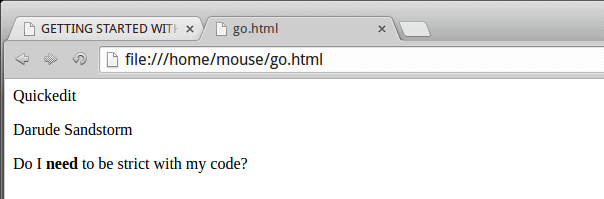

Much like the aforementioned Notepad++, Brackets offers a variety of extensions, which can enhance the basic behavior. The extensions cover a lot of stuff, like the ability to parse CSS, enforce strict code, use various templates, change theme and background, add annotations, work with regular expressions, and more.

Live Preview

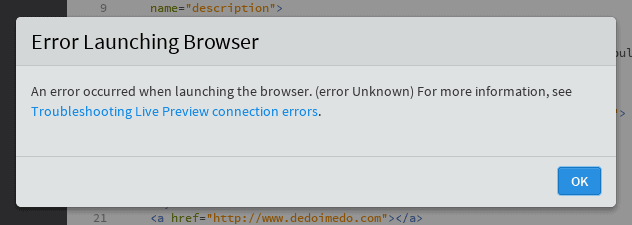

This is one of the more interesting features of this text editor, but it also comes with a big disclaimer. First, you must have Google Chrome installed, because it’s the only browser that Brackets will use to preview data. It will continuously feed changes in your text file to the browser, so you do literally get a live preview. However, this function won’t work if your code does not have a valid syntax, which kind of forces you to write nice, neat, compliant HTML, and you can only preview a single page at a time. So this isn’t a true WYSIWYG, and it’s more like what Bluefish does than other classic editors, and overall, the functionality isn’t that mind blowing, despite its lively [sic] nature.

For me, this feature was sort of a hit and miss and then explode randomly thing. It took me a while to figure out the problem with Chrome connectivity, because you sure don’t expect that kind of limitations. Moreover, I normally avoid reading about products beforehand, so that I can discover how easy and intuitive they are.

Eventually, you will get this running. Brackets is lenient when it comes to HTML code, and you don’t need full head and body declarations to get the necessary previews, but it can be a little restricting, and the constant switching between windows can make your eyes hurt. Then, Chrome crashed once or twice during the testing, so it’s not all peaches and lemons.

Other features

The one thing I really liked is the auto-closing of braces. This can really help you avoid errors when nesting multiple HTML objects, and then suddenly forgetting that one innocent </div>, and then you’re wondering why nothing is working as you expect. All in all, Brackets comes with a lot on its simple, unassuming gray plate, it’s rich in options and tools and extensions, but there are some rough, geeky edges about it that ought to be polished. I guess eventually, you can get to like the program and use it smoothly, but the curve is more bendy than with the typical, classic HTML editors we saw earlier. But then, you won’t ever be so cool using Compozer as you will be when running Brackets. Sort of.

Pandoc Markdown & StackEdit

This sounds like a name of a villain from a cheesy 80s movie. A rogue cousin of Lo Pan, and truth be told, it’s more or less true. What I’m going to show you now will jumpstart your career as a total nerd, on the peril of losing all contact with humanity. But it comes down to the following:

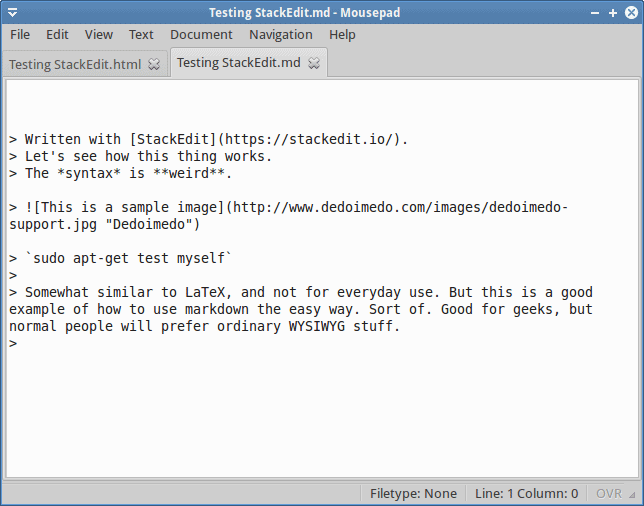

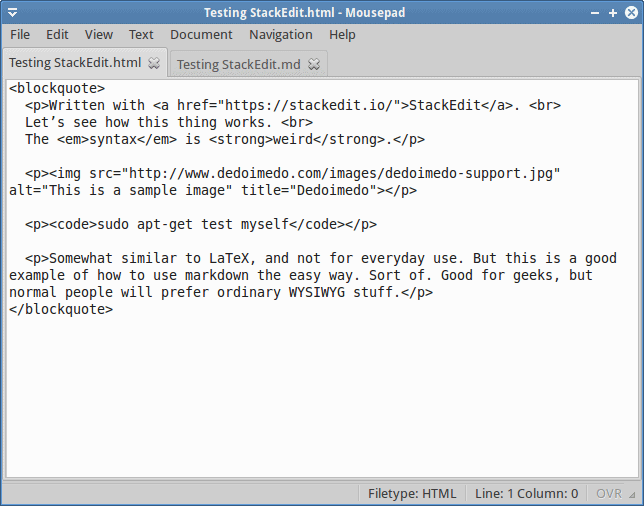

One, there’s a this thingie with a peculiar name called markdown, a markup language with plain text formatting syntax. It’s unto HTML what LaTeX is into itself, only the way code elements are declared is different. When using a markdown processor, you will get a nicely formatted HTML code. Then, you can write HTML in the first place, so why bother?

Exactly. The answer to this question is point number two. If you write markdown text, the way you write LaTeX, sometimes with the optional use of text processors like LyX, you avoid the need to worry about validity of output and layout, you just focus on the text. Indeed, markdown text can be translated into valid HTML, or converted into other document types in a strict manner, something you might not be able to do using your own code. To wit, you use pandoc, a command-line tool that we’ll play with shortly.

Lastly, three, if you find the markdown syntax too restricting, annoying or whatnot, you can use a markdown editor to write as you please, and let the software backend translate your words into the necessary code. To that end, you gain StackEdit, an in-browser markdown editor, realized entirely as a page in your browser. Sounds cool, and we shall explore.

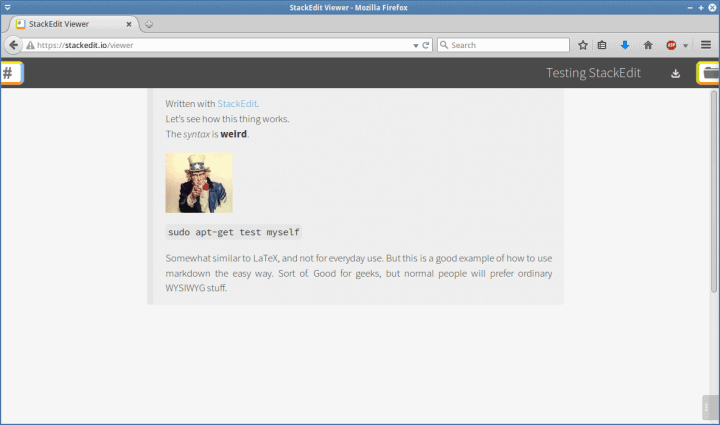

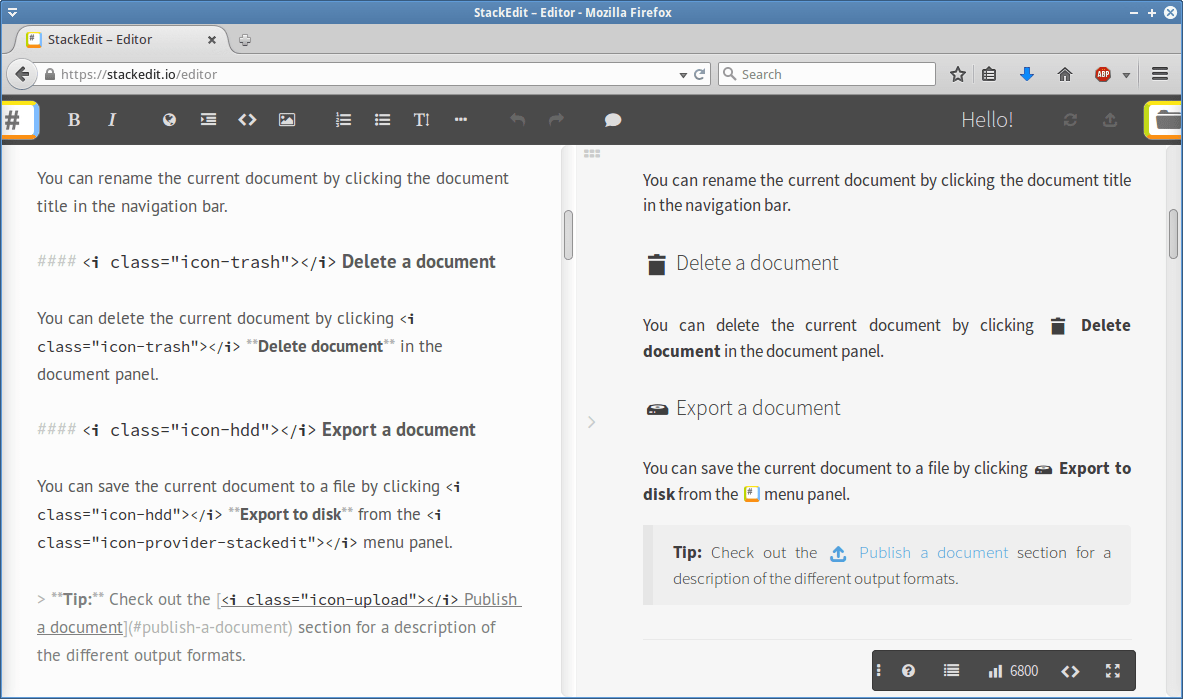

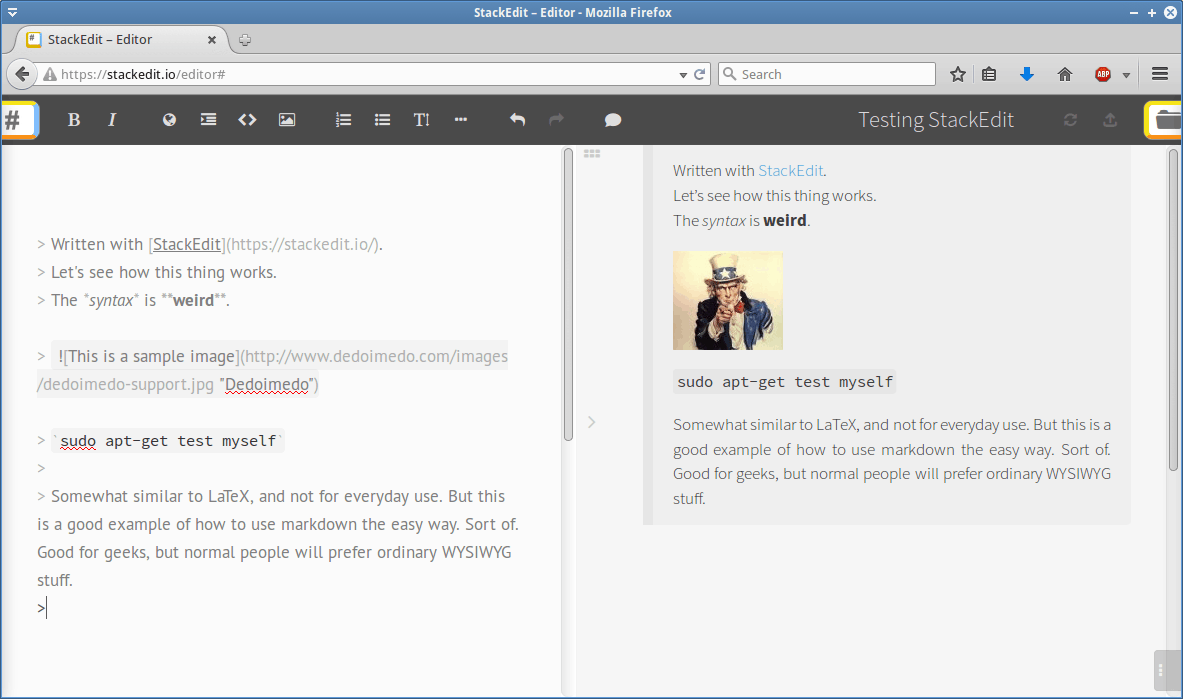

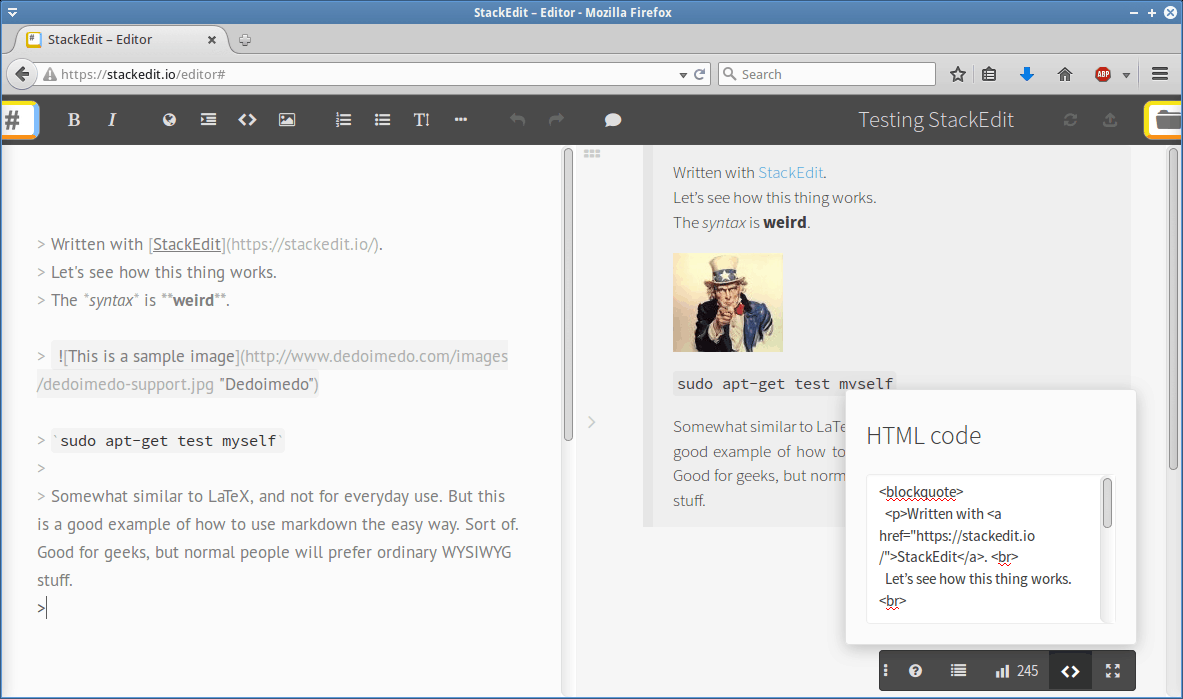

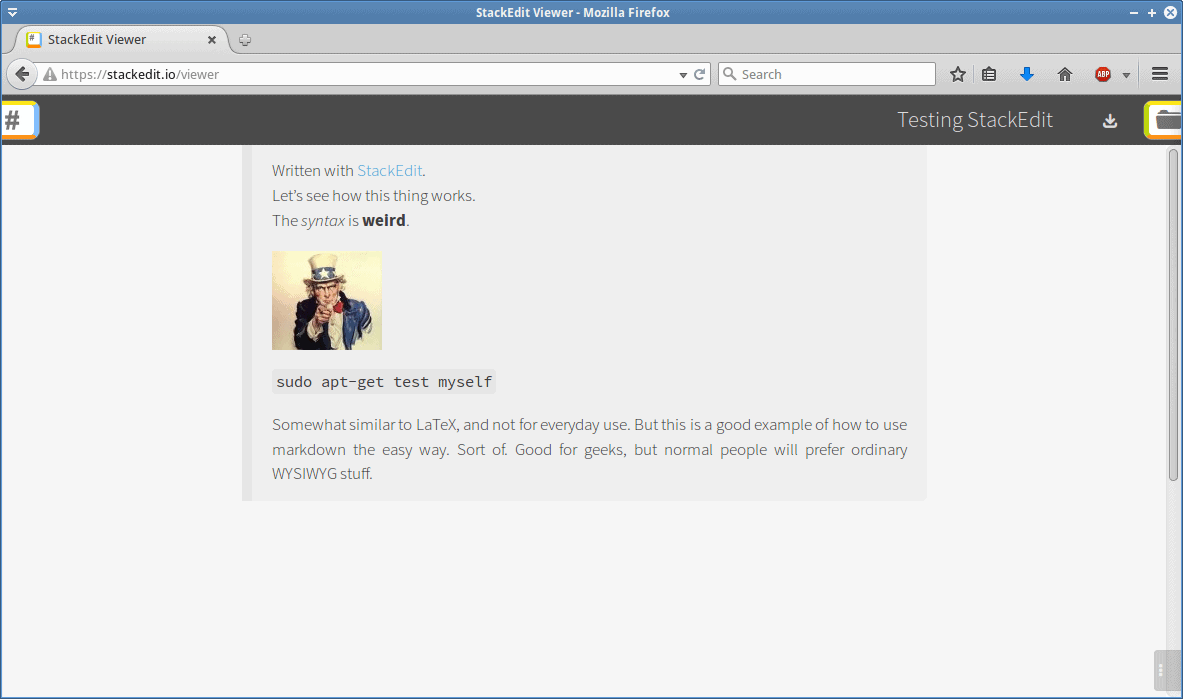

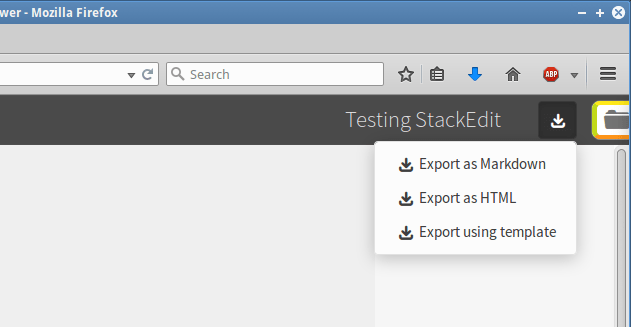

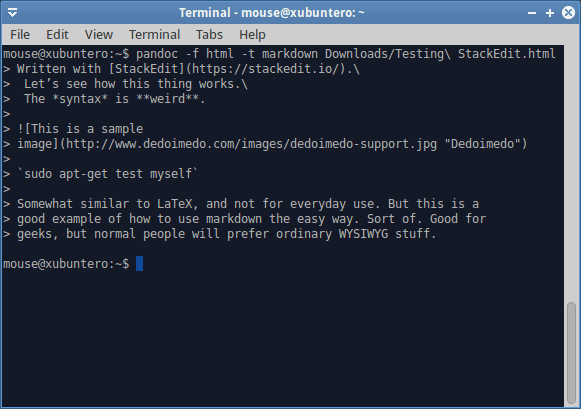

To make life easier for ourselves, let’s begin with the last item. Indeed, StackEdit is an interactive page in your browser tab. Open it and start writing. All of the files you create are saved in the browser cache, so once you’re done, you might want to save or export the files, including HTML, of course. While working in the browser, you can preview your files, use a WYSIWYG like interface side by side with the code pane, and slowly learn and expand your knowledge of markdown.

If you have worked with LaTeX or LyX, you will feel at home. If you have not, you will want to vomit. There’s a wagonload of logic in writing your documents like this, but the problem is with the initial heap of attitude change, unfamiliar code and way of doing things that requires patience and stamina from the users. In the end, you can be extremely fast and elegant, but for new users, it can take many hours of frustration to even type down the first page.

Anyhow, you can export HTML code right away, and after previewing the file, you can save it locally. You can also compare .md and .html files, so you can see the difference in how your text is formatted. The two look different, although essentially, they are the exact same thing.

Is this the superior way of doing HTML? Probably not. You might ask yourselves why bother in the first place. And this is why we must invoke pandoc, to see what it can do. As a tool, it’s available in the official repository of many distributions, so you can grab and install it with ease. Then, you need to dig into the command line, and spend some time reading the man page.

Normally, pandoc writes results to standard output, but it cannot do this for all file types. Moreover, for a complete and hassle-free conversion routine, you must have several other interpreters and modules installed on your Linux system, including several LaTeX utilities and fonts. It really gets nerdy, in a satisfying kind of way. Maybe.

You specify file types (-t), you specify syntax (-f), you then provide an input file, and an optional output file (-o), or redirection, unless you just want the stuff in your command line shell, right there. This is the basic way of doing things. Speaking of output, you cannot use redirection for binary file types, and it will only work for plain text. Let’s see some more stuff.

Pandoc examples

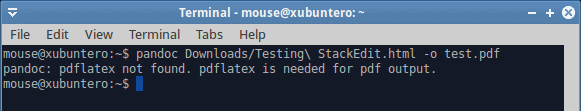

All right, so for instance, a PDF translation might probably fail (-o output.pdf) if you don’t have the right stuff. In this case, pdflatex is missing, but this is a generic name, and it won’t necessary translate into a specific package in your repositories, so you might feel a bit confused.

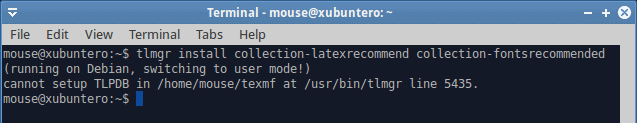

Then, you may already have the LaTeX tools, including the package manager like tlmgr, but it may not necessarily work, and it may throw errors. For instance, if you try to install several recommended font packages, in case you encounter font errors during conversion, yet another obstacle that may deter new users, you will see the following:

! Font T1/cmr/m/n/10=ecrm1000 at 10.0pt not loadable: Metric (TFM) file not found. <to be read again> relax l.100 \fontencoding\encodingdefault\selectfont

And then trying to resolve:

In general, the minimum set of LaTeX packages you need are the following (using Xubuntu as an example):

sudo apt-get install texlive-latex-base texlive-fonts-recommended

This will also install texlive and texliveonthefly packages as dependencies, plus the manager (tlmgr), which are supposed to grab any missing fonts automatically, but it may not necessarily work, so be prepared to some conversion errors. Overall, I must admit that once I had the necessary LaTeX stack installed, everything was working smoothly. Still, it brings a question why you need to bother with markdown and pandoc, if LaTeX does everything in the first place, and LyX is a very powerful editor in its own right?

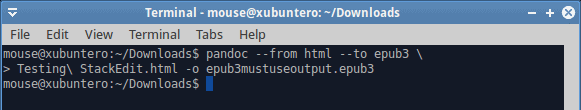

To keep bantering with myself, the answer is, so many conversion formats. So many. Pandoc works with everything. You can convert your text to PDF, Epub, DocBook, OPML, Wiki markup, Open Office XML, ODF, AsciiDoc, and many more. This is what makes it so universally useful and arguably popular. And with markdown as your base, you ought to get high fidelity conversions for all these. Indeed, my tests with PDF and Epub show great results.

Conclusion

Brackets, StackEdit and Pandoc are all heavyweights in the world of HTML, and they bring to the table so much more than just the ability to write text. If your only goal is to have a few rudimentary HTML pages out there, or you prefer a CMS that hides away all the gory details, then by all means, avoid these. Please. Overall, for most people, Notepad++, any classic text editor in Linux, and Blue Griffon will be the optimal mix for their Web development.

However, if you’re looking for a somewhat more challenging experience of mastering your text, with full flexibility to convert, play around, export, tweak, and adjust, with some inconvenience of additional learning, fretting and installation of packages that support this ordeal, then you should invest the required time in becoming an ultra-nerd. Hopefully this article has opened and then closed your braces. Oh that was so witty. Peace. Oh, and for those asking, Plasma 5 official release coming soon!

Cheers.

for an extra notch in the proverbial nerdbelt, please use Commonmark instead of the ambiguos defined original markdown.

http://commonmark.org/

It will never end, will it :)

Dedoimedo