The Browser State

For most people, the choice of the Web browser is a funny formula of I-used-it-first, whatever is installed by default, followed by look and feel, speed, perceived security, and finally, last but not the least, actual functionality. On top of that, users tend to be quite loyal, or rather quite habitual, to their browsers, and they rarely venture about exploring new options and possibilities, even if they might be technologically superior.

I’d like to give you an overview of several top browsers in the Linux world and how they stack against one another across the spectrum of basic requirements that determine our choices. And before you say, boring, I have read this a million times over, I know everything there is about my browser(s), you might want to take a look nonetheless. And we will do a short comparison to Windows versions of the very same products.

Firefox

Firefox is the darling of the Linux world, and virtually every distribution comes with it. Some KDE-flavored operating systems offer only installer scripts, while a few omit it altogether. However, I cannot think of even one distribution that does not have Firefox in its repository.

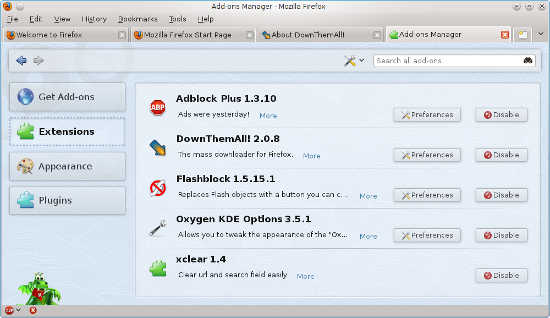

One of the leading features of Firefox is its extensibility. It began its way as an Internet Explorer alternative by offering tabs, and more importantly, add-ons that allowed you to enrich your experience beyond the standard set of buttons and options. Fast forward a handful of years, other browsers are trying to follow suit, but Firefox still leads by a fair margin when it comes to its extras. There’s practically no domain of use and interest that does not sport at least one extension.

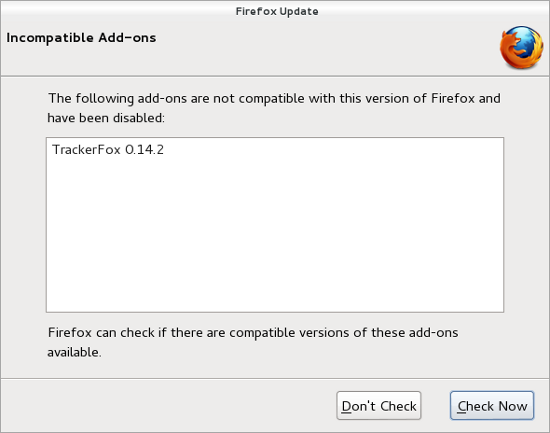

Beware, ’tis a double-edged sword. This powerful capability can also be used against you. With Firefox adopting a more frequent update cycle, some of the extension developers find it hard to keep face, so you end up with incompatible add-ons. There’s nothing more disheartening, apart from maybe natural disasters and war, than learning your favorite browser will behave ever so slightly differently than it did yesterday.

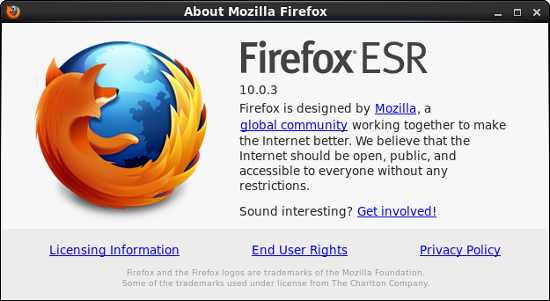

The relatively rapid update cycle also makes it difficult for businesses to adapt and make necessary changes, which is why the Extended Support Release (ESR) version was created. For instance, this one comes included in RHEL6 and CentOS 6, allowing you one year of peace of mind in between the updates.

Security wise, from a pragmatic standpoint, Firefox is just as secure as the rest of them, especially on Linux. The browser patching will be determined more by your distribution repository refresh policy rather than the vendor timetable.

Comparing to Windows, you would assume there are no differences between the two versions. However, some extensions are available only for Windows users. On the other hand, in Linux, you actually get a proper 64-bit version of the browser should your distro happen to be 64-bit. Furthermore, the self-update mechanism in Linux is replaced with the overall system update functionality, so you will not really be upgrading your plugins or the browser itself through its internal menus. Moreover, I do not recall Mozilla automatically blacklisting insecure plugins in any of the distributions. I have seen this happen in Windows, not in Linux.

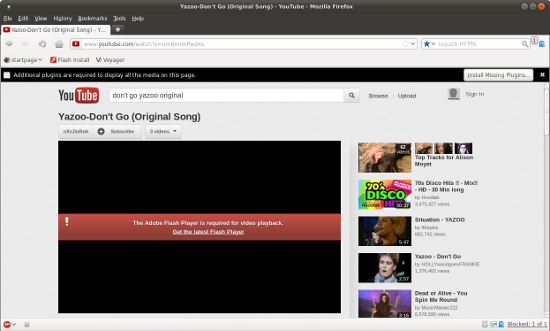

Indeed, the fact some distributions choose to ship their products with some proprietary plugins removed, or not installed, may pose some difficulty for less knowledgeable users. How do you go about installing Flash or maybe Moonlight, if you are still not familiar with the overall update mechanism?

Speaking of Flash, with the recent Adobe decision to drop the standalone plugin in favor of the new programming interface called Pepper, which will only be available in Chrome, you may need to reassess your browser usage some four or five years down the road, unless all Flash content is replaced by HTML5 till then.

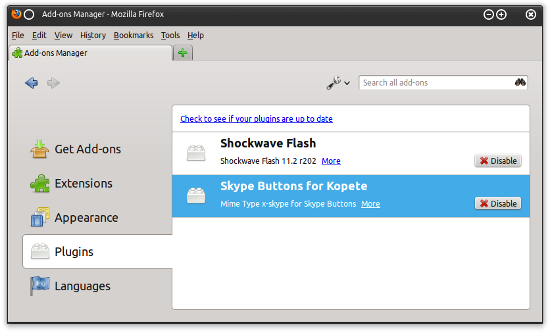

On the other hand, Firefox offers Skype Buttons integration, which other candidates in this article do not. So you do gain some, lose some, and it’s definitely not trivial or linear, especially if you throw Windows into the lot.

From the stability perspective, Firefox is fairly robust, although I have seen one or two cases where the browser or one of its plugins crashed. It does not happen quite often, and it mostly depends on the overall distro integration.

All in all, Firefox has everything most people will need, with a million extensions to fulfill their every need. Some of the problems you may encounter will include incompatible add-ons and plugins, mostly resulting from timing and ideo-political decisions rather than any technological flaws.

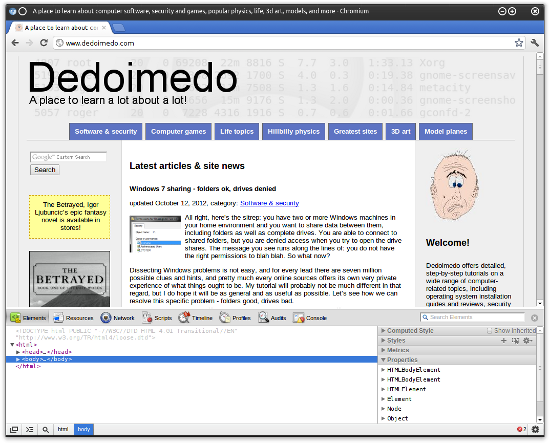

Chrome and Chromium

It is important to note that these two, despite the name similarity, are two separate products. One of the closed-source Google product using some parts of the open-source Chromium project, while the latter is a browser built entirely on the open portions of the code.

To that end, most repositories will feature Chromium in their arsenal, while Google Chrome will be available by manually adding new software sources to your distribution. Automatically, this poses some problem for new, less skilled users. Then again, are they likely to use anything that is not installed by default? A dinosaur and a bird problem. A social worker and social problems problem. Well, you get the idea.

The Chrome family prides itself on a very rapid upgrade cycle, but like Firefox, the internal mechanism is dormant on Linux. Unlike Firefox, the extreme simplicity of the browser means you will rarely if ever see anything break on the surface, so you may assume Chrome sports a higher level of compatibility. To some extent, this is quite true.

The downside is that Google’s browser, as well as its gray-colored open-source counterpart do lack in some of the more obvious features you will find in Firefox. Or at the very least, they are less easily found. For example, bookmarks. How do you go about these? Yes, they are there, but would you find them if you were a first-time user? Likewise, extensions in general, and adblocking in particular, are a tiny bit more difficult in Chrome. Bias may apply without further notice.

In some instances, Chrome will ask you what default search engine you wish to use. In contrast, Firefox will usually default to whatever the distribution developers choose, mostly for financial reasons. Some may opt for Google, others for Yahoo, others yet for Ask and other providers. Do note that some search engines do not forward all queries that well when typed directly into the address bar, compared to organic searches.

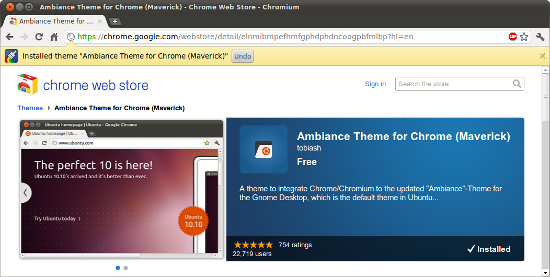

When it comes to add-ons, Firefox leads by a wide margin, but Chrome is getting better all the time. One advantage this browser has over the Mozilla’s flagship product is that most extensions do not require a browser restart. Moreover, you specifically get extensions that help with the visual integration with the native system theme and functionality, or if you like, you can use its own rather OS-agnostic looks.

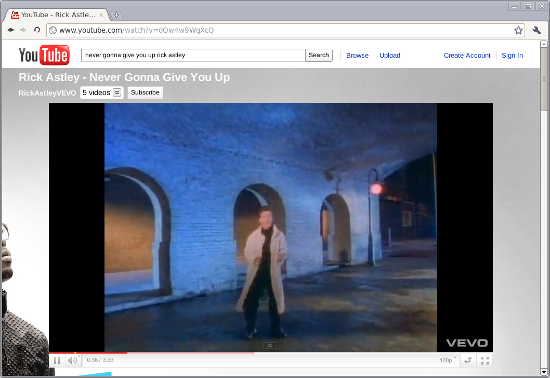

Chrome also ships with its own Flash version, as we have elaborated earlier, so even if your distribution adheres to the free software only policy, you will be able to enjoy rich media online, however, you will still have to manually setup the software sources and install the browser. Another strong point of the Chrome family is the very powerful set of developer tools, which lets you debug and trace the loading times and errors in your Web pages. Most people will never need these, but they are quite handy.

Chrome and Chromium are perfectly sane and useful options for Linux users. The migration between operating systems is seamless, and if you are signed in, your customization and preferences will be preserved across all devices and instances of your browser. The extensions are still a bit lacking. However, the plugin support is very reasonable and bound to get even better.

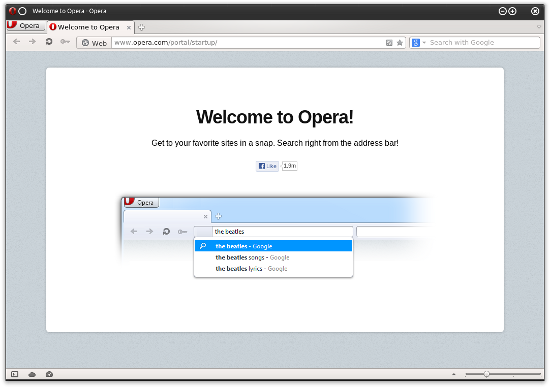

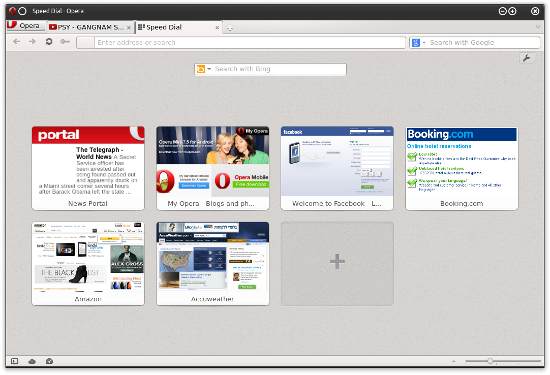

Opera

This browser does not feature in most repositories, so you are much less likely to come across it in your distributions. The installation and maintenance are entirely manual, just like Windows, which could definitely deter you from trying it in the first place. If you can get past the clunky stage, you will get a fairly decent 64-bit browser. Opera has what all the rest offer, too, tabs, tabs dial, sync, private mode, and other basics. It also comes with solid HTML/CSS support. However, you cannot escape the feeling this is first and foremost a Windows product. The theme integration and the overall feel are not on par with either Firefox or Chrome.

Truth to be told, Opera is more than just a browser; it’s an Internet suite, and you also get mail and chat clients bundled with the product, although you must be signed into Opera to utilize them. On the other hand, the extensions are virtually nonexistent, so what you see if what you get.

Opera on Linux does not support Silverlight (Moonlight). This plugin, in either 32-bit or 64-bit flavor is only available for Firefox and Chrome, up to version 4, so if you’re looking for Windows-like capability, this one lags behind.

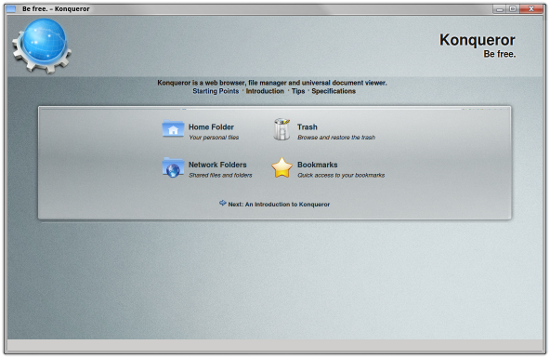

Konqueror and rekonq

Placing these two side by side might not be fair, but they are like father and son. Konqueror has been the steadfast KDE workhorse for many years, part browser, part file manager, while the son aims to be a lean and sleek browser-only product. Still, you cannot ignore the many commonalities in their design and feel.

If you are used to running either Firefox or Chrome, you will notice an instant difference when you switch over to the other two. The notable changes include a new font, a somewhat entirely subjective, slightly less intuitive arrangement of GUI elements. My experience shows less than ideal rendering of some of the Web pages and some trouble finding the right options in the menus.

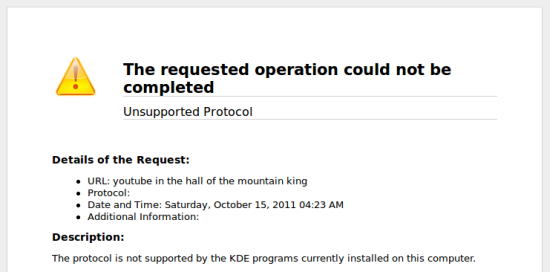

Konqueror does have the added benefit of being able to browse local directories and network shares, however you might hit an error if you try to perform a search directly in the address bar, as the query might to be forwarded to the default search engine and instead, might be misinterpreted as an unsupported protocol. The problem is further compounded by the search engine choice.

As far as visual appeal goes, Konqueror is less modern and sleek than either Firefox or Chrome. This may not necessarily be a showstopper, but it does matter in this world of ours. Moreover, I have seen it crash one or two times, but this might be KDE-centric rather than the browser’s fault.

Rekonq is more modern-looking. It is somewhat reminiscent of Google Chrome, but it feels a little more cluttered, little less polished. The tab dial always shows only four preset pages. If you want to add new ones, you must manually click to add, then browse to the relevant page.

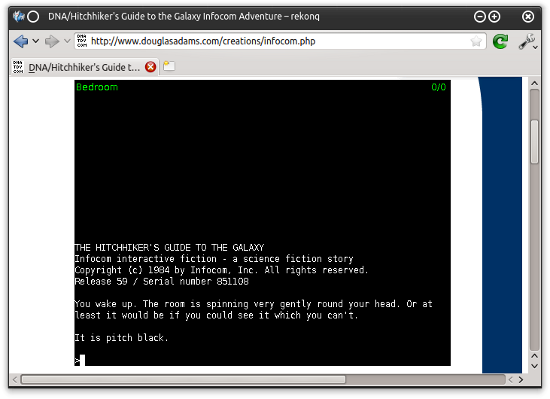

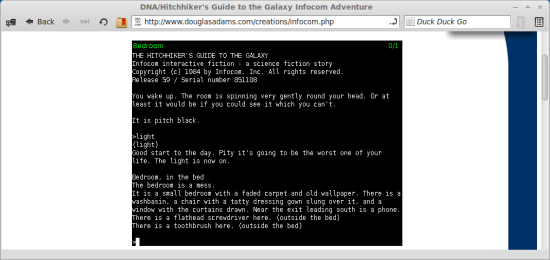

While rekonq supports Java, the actual compatibility is less than perfect. For example, even though both versions 6 and 7 of the OpenJDK framework were installed, as well as the IcedTea Web plugin, they did not quite work as expected in rekonq. Firefox and Chrome did not have any problems, and I was able to use and interact with Web applets. On the other hand, rekonq did load the oldie but goodie Douglas Adam’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Java game, but I was unable to type text and switch on the lights.

Likewise, Moonlight and Skype support is out of scope here. In this regard, rekonq is behind the competition. In general, comparing to Windows, for all browsers, the plugin support, including media player and PDF integration, is somewhat less emphasized and developed. Moreover, on Linux specifically, I noticed that most plugins are 32-bit, while both the underlying Linux system and the browser are 64-bit. Not quite what you would expect.

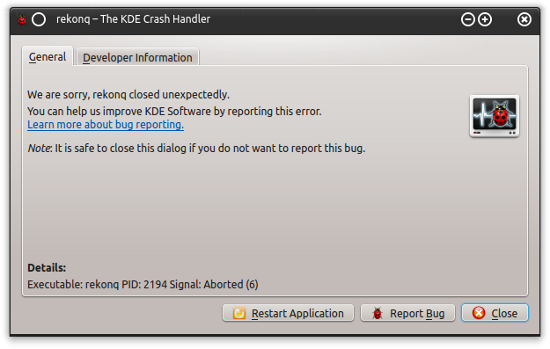

My short history with rekonq is rift with crashes, especially after trying to use some of the more exotic plugins, like the example above. The combination of a somewhat non-standard interface, a lack of plugin support and stability do make rekonq a dubious choice for most people, despite the sleek approach.

Midori

Midori is a lightweight browser mostly geared for non-KDE, non-Gnome environments. Midori is based on WebKit, it comes with a long list of features and supports a limited number of extensions. You also get private browsing, Maemo integration for mobile devices and a speed dial. My experience shows the browser is quite fast and elegant, but its rigid interface may deter tweak-hungry users. It also worked well with Flash, Java, embedded music, as well as PDF documents.

So you might ask, what’s missing? Well, Midori is little known, less popular, and beyond its set of features and capabilities, you will find little else. As a finite product, it does what’s expected of it, but if you’re looking for any level of customization, look elsewhere.

Conclusion

You may feel like the conclusion of this article was known before it was written. Still, the article does expose several interesting facets you may not have thought about, like the 32-bit and 64-bit versions of browsers and their plugins, the overall plugin support across different browsers, distributions and Linux vs. Windows, the varying capabilities in different operating systems.

Firefox is the lead browser in Linux, and it’s quite evident. It is robust, useful and immensely extensible. Chrome is probably the most uniform product across the board, with the best sync, but it does need more add-ons and customization to appeal to nerdy souls. The list continues with several other, let’s call them second-choice browsers, which all have their merits, mostly looks and speed, but the core functionality is somewhat flawed or lacking or entirely missing. Which means your choice will be driven by your taste and actual needs.

Well, I hope you enjoyed the article. The list is far not exhaustive, and there are many other products we could have tested, but even so, today’s picks are more than enough to get you started and perhaps thinking. See you around.

Although Firefox has pretty much always been my main browser in both Linux and Windows for more years than I care to state (erm…I can recall when you had to pay for Opera or use the free ad-supported version), I’ve always kept a secondary browser on hand. Currently, it’s Google Chrome.

Since AdBlock Plus (from the author of the Firefox version) and DoNotTrack+ are now available as Chrome add-ons I would actually consider Chrome as a main browser except for one thing–no “zoom text only” feature. Firefox has that and it’s essential for my old(er) eyes. Oh, by the way, Firefox 16 now has all the developer tools that Google Chrome has so that’s not a reason to switch to Chrome any longer. Just saying. :-D

As far as the other lesser known browsers are concerned, I absolutely agree although Gnome 3.6′ “Web” browser (basically the next version of Gnome’s Epiphany browser) works fairly well for a browser that does not support Flash. On the other hand, it has full HTML5 support built in…using the phrase “full HTML5 support” with lots of leeway you understand.

Good article as usual,

From a dedicated follower of your Dedoimedo site.

What is this madness? No browser has –FULL– HTML5 support!!!!!

Y.A. – If you read the last line of my comment you’d understand I was being a bit facetious when I said that:

“…using the phrase “full HTML5 support” with lots of leeway you understand.”

Okay?

Madness? This is Sparta!

Dedoimedo

I’ll never use Chrome/Chromium until Google becomes humble enough to offer users what they need, e.g., a bookmarks sidebar and toolbar. The thinking seems to be – as ad nauseam in the tech industry – “We’re engineers. We’re logical. We know what’s good for you.” Sadly, like the old joke about the Catholics in heaven, they don’t know anyone else is there.

Exactly right. Form should follow function (even though “function” follows “form” in this sentence!). Unfortunately, a lot of people are stupid and arrogant. Mark

The no-toolbar approach is absolutely right for me. I have seen so many Firefox/IE users that are not computer savvy with an extremely cluttered toolbar (of course thanks to bundled installers, but anyway, they often do not know how to disable the toolbar installation.)

I have used Firefox for years, but when Chrome emerged with seperate processes for tabs (even IE implemented this earlier than Firefox), incognito windows that don’t disrupt the whole damn browsing experience, speeeeeed, integrated web tools, better omnibox, “Click to play”, and the download progress clock :-), I soon switched. First, I used Iron, then Chromium (which is a pain to upgrade and to integrate the PDF/Flash plugins) and finally have switched to Chrome recently. The amount of privacy/non-privacy is now okay for me.

I like the simplistic approach very much and I hope they keep it that way. I also like the Save-to-PDF feature and rendering in seperate threads. Since my netbook is quite constrained on resources, thanks to Chrome, I can keep dozens of tabs open, listen to music on YouTube or PromoDJ, quickly open a incognito window when I do some account managing/ebanking, and nonetheless can browse the web smoothly. Furthermore, I even don’t have to worry about f**king Flash crashes.

However, it’s quite annoying that the user profile is not saved in %appdata%, but %localappdata%. Now I use Firefox only as a host for cool addons like DownThemAll, ChatZilla, and SQLite Manager.

Opera browser for me since version 9, and it’s perfectly integrated into my Ubuntu 12.04 machine (of course with the installation of the ppa).

Good article. However, it is still unclear to me, as a less knowledgeable user, what are the real differences between Chrome and Chromium.

For all intents and purposes, they’re the same thing, except Chrome has Google branding on it, while Chromium has nothing closed-source attached.

That’s how I understand it anyway. There might be other differences, but I use Seamonkey, so whatever.

What about Iron?

SRWare Iron: The browser of the future – based on the free

Sourcecode “Chromium” – without any problems

at privacy and securityhttps://www.srware.net/en/software_srware_iron.php

Old linux user. Personally I use firefox on all my systems since firefox 2 and I can’t even imagine how my internet experience would be without mozilla or netscape earlier. For me Chrome and Chromium is a useless alternative for young heepsters who like minimal interfaces, it is a resource heavy browser full of ads and with no add-ons and extensions functionality.

Opera is pretty amazing, the fastest browser and my second browser of choice working perfectly in hi-end or slow machines with alot of the firefox’s usability of plugins and add-ons. It’s my primary browser for systems with low processing speeds and limited memory such as my netbooks and smartphones! So far I used it with almost every operating system I have: win, mint, ubuntu, kubuntu, debian, slack, suse, puppy, macpup, android, bada you name it..

Never fails. and it offered from the start unique woking features!

The Opera turbo feature allows fast navigation even when you browse from a slow sharing puplic wifi or from a dial-up 3g cellphone connection, by-passing firewalls and network imposed limits.

I also found of extreme importance the feature of saving opened pages to cache for next session so that you don’t have to load anything at the start to be excellent allowing me to continue navigation right where I was in my past session without wasting time to load everything again.

On KDE, I rarely but still use Konqueror though somehow old and nostalgic. With rekonq I used to have crashes almost on every use, (note to dev.) rename crashkonq maybe? It gets more stable nowadays but no thanks, too many bad memories..

Seamonkey and Midori is the future of the low resource browsers. I found Midori cute and enjoyable and I always keep it as backup installed browser in case everything else fails.

Cheers to Igor for his hard work!

I’ve used Firefox since it began (and Netscape prior) but lately the rapid release updates are really getting on my nerves. I can no longer get the themes I like and it takes a while to get add-on updates, sometimes. Printing from it has been very flaky for the last several versions, too. Still, there are a couple of add-ons I can’t live without and don’t think I can get with other browsers. I hate Chrome. I haven’t tried Opera in a long time so maybe I’ll give it a try as a backup, at least. I have no need for Silverlight or Moonlight. Thanks for the article.

For a bit of Midori customisation, try right-clicking on the toolbar. You’ll be able to add a menu, or bookmarks bar. You can also change the icons’ layout on the toolbar using an extension. That’s about it, though, but it’s already enough for me.

I use seamonkey as my primary browser everywhere. Wonder why the author did not even mention this in his article. But then again seamonkey is basically a fork of the mozilla suite, so there is not much difference from firefox

Exactly. Moreover, Seamonkey is a fully fledged suite.

Dedoimedo

I used seamonkey as a backup browser in previous versions of mint.. I’m currently using mint 13 mate, and I cannot find it in the software packages or the snaptic package manager.. I tried a closed source version and added wine my operating system.. wine did not load correctly and wound up being a disaster.. I had to reload my system to make everything smooth operating again.. any suggestions on this??……………… Picker

You can get it from ubuntuzilla site

http://sourceforge.net/apps/mediawiki/ubuntuzilla/index.php?title=Main_Page

echo -e “ndeb

http://downloads.sourceforge.net/project/ubuntuzilla/mozilla/apt all

main” | sudo tee -a /etc/apt/sources.list > /dev/null

sudo apt-key adv –recv-keys –keyserver keyserver.ubuntu.com C1289A29sudo apt-get updatesudo apt-get install seamonkey-mozilla-buildBut I use Netrunner4.2, It works well